The issue of whether the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) preempts state laws is complex, with numerous courts ruling differently on the issue for a wide variety of different state health insurance regulations.

In recent years, state laws regulating pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) have become a significant point of contention. The industry faces growing scrutiny with minimal federal regulation, resulting in a surging number of PBM laws nationwide; all 50 states have enacted at least one PBM-related law between 2017 and 2023. In addition, litigation surrounding the management of prescription drug benefits has increased as new transparency laws provide employees with more information regarding health care costs. As these costs continue to rise and state governments seek ways to improve transparency and curtail expenses, PBM-related litigation will likely increase.

Whether ERISA preempts a particular regulation will ultimately depend on the applicable jurisdiction and the scope of each law’s specific provisions. Because there is no one-size-fits-all ERISA preemption analysis for state laws that regulate insurance, this guide provides a general overview of how courts have applied the analysis in the context of state laws regulating PBMs. It is important for insurers, providers and employers as group health plan sponsors to become familiar with this area of law as it continues to evolve.

Background

Private health plans contract with PBMs to administer their prescription drug benefits. Health plans generally rely on PBMs to process claims, develop pharmacy networks and negotiate rebates from drug manufacturers. As the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit noted, PBMs administer drug benefits for an estimated 270 million people nationwide.

Increased State Regulation

Over the past few years, researchers and stakeholders have questioned certain PBM practices, such as retaining a share of drug manufacturer rebates and using spread pricing. In response, states have begun to enact legislation addressing PBMs, which has triggered the issue of whether ERISA preempts these state laws.

Reason for Preemption

The purpose behind ERISA’s preemption provision is often cited by courts as a factor in the decision of whether preemption exists. ERISA was enacted to make employer-provided benefits more secure, and preemption allows plan sponsors to operate under a uniform body of law without having to tailor plan benefits to a patchwork of conflicting state laws. It also makes wide-ranging remedies that are otherwise available under state law inapplicable.

Larger, self-funded companies with multistate plans can rely on ERISA rather than the emerging state laws governing prescription drug benefits, particularly in the PBM context. However, the lack of transparency in the PBM industry often leaves employers, as plan sponsors, in the dark about the negotiations between PBMs and third parties like drug manufacturers. If they are not privy to these negotiations, it can make it difficult for plan sponsors to determine whether their PBMs’ practices and agreements are reasonable, which they have a fiduciary duty to ensure.

ERISA Preemption Analysis: Summary

At a very basic level, the ERISA preemption analysis can be summarized as follows:

- Broad preemption of state laws that “relate to” ERISA plans

ERISA’s preemption provision supersedes any state laws that “relate to” ERISA employee benefit plans. Essentially, this means that states aren’t allowed to pass laws that cover the same things that ERISA covers, so that there are no conflicts between state and federal law. - Savings clause exception

There is an exception to the preemption provision, referred to as the “savings” clause, which “saves” state laws that regulate insurance companies (and similar entities) even if they “relate to” ERISA plans. - Deemer clause: limits to the exception

The “deemer clause” limits the scope of the savings clause by exempting self-funded plans from state laws that “regulate insurance” within the meaning of the saving clause. In other words, self-funded employee benefit plans cannot be deemed insurance companies for this purpose. - End Result

Fully insured ERISA plans are indirectly subject to state insurance law through the laws that govern their insurers’ policies. However, ERISA generally preempts state laws that relate to self-insured health plans.

When Does a State Law “Relate to” an ERISA Plan?

A state law “relates to” an ERISA plan if it has:

- An “impermissible connection with” an ERISA plan; or

- A “reference to” an ERISA plan.

When Does a State Law Have an “Impermissible Connection With” an ERISA Plan?

In determining whether a state law has an impermissible connection with ERISA plans and is thus preempted, courts have asked the following:

- Does it govern a central matter of plan administration?

- Does it interfere with nationally uniform plan administration?

If the answer to either of these questions is yes, the state law is preempted. As the U.S. Supreme Court stated in Rutledge v. Pharmaceutical Care Management Association (PCMA), the connection- with standard is “primarily concerned with preempting laws that require providers to structure benefit plans in particular ways, such as by requiring payment of specific benefits or by binding plan administrators to specific rules for determining beneficiary status.”

Examples of When an Impermissible Connection Exists (Preempted)

The Rutledge Court cited the following as examples of state laws that have an impermissible connection with ERISA and are thus preempted:

- Laws that require providers to structure benefit plans in particular ways, such as by requiring payment of specific benefits or binding plan administrators to specific rules for determining beneficiary status; and

- Laws whose acute, albeit indirect, economic effects force an ERISA plan to adopt a “certain scheme of substantive coverage.”

As another example, the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals case of PCMA v. Glen Mulready held that an Oklahoma law was preempted by ERISA because a pharmacy network’s scope (which pharmacies are included) and differentiation (under what cost-sharing arrangements those pharmacies participate in the network) are key benefit designs for an ERISA plan and thus have an impermissible connection with ERISA plans.

Examples of When an Impermissible Connection Does Not Exist (Not Preempted)

According to Rutledge, state regulations that merely increase costs or alter incentives for ERISA plans without forcing plans to adopt any particular scheme of substantive coverage are not preempted by ERISA. Here are a couple of examples:

- A state law that incentivizes, but does not require, plans to follow certain standards for apprenticeship programs; and

- A state tax on gross receipts for patient services that simply increases the cost of providing benefits.

In Rutledge, the Court upheld state regulations authorizing pharmacies to refuse to dispense prescriptions if the PBM’s reimbursement would be less than the wholesale cost paid by the pharmacy.

Subsequently, the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in PCMA v. Wehbi upheld state regulations that, among other things, limited the accreditation requirements that PBMs could impose on pharmacies as a condition for participation in their networks and required PBMs to disclose basic information to pharmacies and plan sponsors upon request. The 8th Circuit found that these constituted, at most, regulation of “noncentral matters of plan administration” with “de minimis economic effects.”

When Does a State Law “Refer to” an ERISA Plan?

In determining whether a state law “refers to” an ERISA plan, courts have examined the following:

- Does it act “immediately and exclusively” upon ERISA plans? In other words, is the state law claim premised on the existence of an ERISA plan?

- In Rutledge, a PBM law did not act immediately and exclusively upon ERISA plans (and thus was not preempted) because it applied to PBMs whether or not they managed an ERISA It affected plans only insofar as PBMs may pass along higher pharmacy rates to plans with which they contract.

- Is the existence of an ERISA plan essential to the state law’s operations?

- Rutledge clarified that the existence of ERISA plans is essential to a law’s operation only if the state law cannot apply to a non-ERISA

- For example, the 9th S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Bristol v. Cigna held that the plaintiff was “seeking to obtain through a [state contract] remedy that which [it] could not obtain through ERISA[,]” which triggered preemption.

Exception to Preemption: Savings Clause

ERISA’s preemption provision contains an exception, referred to as the “savings” clause, which “saves” state laws that regulate insurance even if they relate to ERISA plans. The Supreme Court, in Kentucky v. Miller, established a two-part test to determine whether a law is saved from preemption:

- The state law must “be specifically directed toward entities engaged in insurance”; and

- The state law must “substantially affect the risk pooling arrangement between the insurer and the insured.”

In other words, state laws that regulate insurance carriers (and similar entities, such as HMOs) are generally not preempted by ERISA.

Result of Savings Preemption Exception

Fully insured ERISA plans are indirectly subject to state insurance law through the laws that govern their insurers’ policies. However, ERISA generally preempts state laws that relate to self- insured health plans because of the “deemer” clause, discussed below.

Limits to the Preemption Exception: Deemer Clause

The “deemer” clause exists to prevent states from improperly invoking the saving clause to skirt preemption. The Mulready court summarized its function as follows: “While ERISA’s savings clause carves out exceptions from the broad reach of ERISA preemption, the so-called ‘deemer clause’ limits the scope of the savings clause.” It does this by exempting self-funded plans from state laws that “regulate insurance” within the meaning of the saving clause. As a result, self-funded ERISA plans are exempt from state regulation insofar as that regulation relates to the plans. As the Supreme Court noted in FMC Corp. v. Holliday:

“State laws that directly regulate insurance are ‘saved’ but do not reach self-funded employee benefit plans because the plans may not be deemed to be insurance companies, other insurers, or engaged in the business of insurance for purposes of such state laws. On the other hand, employee benefit plans that are insured are subject to indirect state insurance regulation.”

Current Impact

The extent to which Rutledge may or may not abrogate state laws that involve different methods of regulating PBMs is currently unclear. Unfortunately, it is difficult to predict ERISA’s preemptive effect on such laws, given the current U.S. Circuit Court split on how broadly to apply ERISA preemption

to state PBM regulations. Rutledge indicated that states could enact certain PBM regulations, even if the effect is that it increased plan costs, so long as the law did not force plans to adopt a certain scheme of substantive coverage. Applying Rutledge, the 8th Circuit in Wehbi held that ERISA did not preempt a state law regulating PBMs and third-party payers. However, the 10th Circuit in Mulready expressly disagreed, holding that a similar PBM regulation was preempted by ERISA. Oklahoma Insurance Commissioner Glen Mulready has petitioned the Supreme Court for a review of the case, for which a coalition of 32 state attorneys general have filed amicus briefs in support. Whether the Supreme Court will review the case remains to be seen, although a ruling clarifying the issue would be helpful.

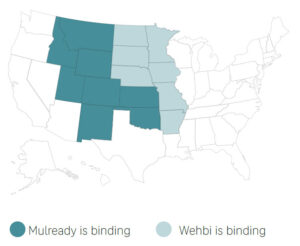

Accordingly, the status of state PBM regulations remains in flux, and their validity will ultimately depend on the scope of each law’s specific provisions. The Mulready 10th Circuit ruling is binding in states within its jurisdiction (Oklahoma, Kansas, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and portions of Montana and Idaho), and the 8th Circuit’s ruling in Wehbi is binding in states within its jurisdiction (Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota). As such, PBMs and insurers in those states should carefully examine their existing PBM laws in light of each respective ruling.

Accordingly, the status of state PBM regulations remains in flux, and their validity will ultimately depend on the scope of each law’s specific provisions. The Mulready 10th Circuit ruling is binding in states within its jurisdiction (Oklahoma, Kansas, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and portions of Montana and Idaho), and the 8th Circuit’s ruling in Wehbi is binding in states within its jurisdiction (Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota). As such, PBMs and insurers in those states should carefully examine their existing PBM laws in light of each respective ruling.

In addition to monitoring state legislation, there are myriad bipartisan bills at the federal level that employers should keep an eye on, such as the “Lower Costs, More Transparency Act.” This bill would require PBMs to semiannually report certain information on spending, rebates and fees associated with covered drugs to health plan sponsors. It would also require contracts with PBMs for employer-sponsored health plans to allow health plan fiduciaries to audit certain claims and cost information without undue restrictions. The bill has not yet been passed and is currently working its way through Congress, as are others calling for similar PBM oversight.

Implications for Plan Sponsors

As stated above, plan sponsors in all states should continue to monitor state regulation of PBMs as this area of law continues to evolve. The potential impact on employee benefit plans could be far-reaching as the courts continue to apply Rutledge to various state laws regulating PBMs, which could include other entities like third-party administrators.

According to a recent report to Congress from the U.S. Government Accountability Office, state regulators are seeking broad regulatory authority to enact laws relating to PBMs, and certain regulators have stressed the need for robust enforcement of PBM laws. It seems state legislatures will continue to ramp up their efforts to regulate the PBM industry. This increase, combined with the uptick in group health plan fiduciary litigation involving the management of prescription drug benefits, means plan sponsors must be vigilant in ensuring they are meeting their fiduciary obligations when it comes to managing prescription drug costs under their health plans.

One of the most important ways employers can demonstrate that they have carried out their fiduciary responsibilities is by having a formal process of selecting and monitoring their plan service providers, especially PBMs. Unfortunately, the lack of transparency in the PBM industry has made this a hard task for employers, and even those who provide sufficient oversight are reticent to change PBMs to avoid disruptions in the prescription drug benefits they provide to their employees.

Nonetheless, ERISA requires fiduciaries to prudently select and monitor plan service providers while considering various factors, including the service provider’s fees and expenses. The duty to act prudently is one of a fiduciary’s central responsibilities, and more fiduciary litigation regarding plan sponsors’ management of its prescription drug benefits is expected. In their role as group health plan sponsors, employers should use this time to establish and document the processes they use to select and monitor their PBMs and consider working with outside counsel when doing so. Other ways to ensure compliance include:

- Establishing a fiduciary committee;

- Monitoring service providers;

- Recording meeting minutes;

- Regularly reviewing plan documents;

- Evaluating third-party service providers thoroughly;

- Reviewing third-party agreements and ensuring they are sufficiently detailed to include things like the hiring process, applicable plan fees and contractual obligations;

- Scheduling routine trainings and meetings for plan fiduciaries; and

- Establishing and documenting claims procedures that plan fiduciaries must follow.

Thorough documentation of an employer’s decision-making process as it relates to their PBMs will put the employer in the best position to defend any potential fiduciary duty breach claims as litigation surrounding the management of prescription drug benefits continues to work its way through the court system.

This document is not intended to be exhaustive nor should any discussion or opinions be construed as legal advice. Readers should contact legal counsel for legal advice. © 2024 Zywave, Inc. All rights reserved.